Esperanto is (Not) Dead!?

About the Enduring Discrepancy Between the Perception of Esperanto as a Language Without Culture and its Extraordinary Cultural Achievements

Throughout the history of Esperanto, its proponents have been confronted with the criticism that they are promoting a language that cannot develop a sustainable culture, because its speakers are not an ethnically or culturally definable entity or based in a geographically unified area. The actual cultural achievements of Esperanto speak an entirely different language, both with regards to the cultural output within the Esperanto movement and the cultural impact Esperanto has been having on the world. The lecture will focus, among other topics, on the field of publishing in Esperanto.

Ulrich Becker is the principal of the publishing house Mondial that specializes in books in and about Esperanto and publishes one of the movement’s leading literary magazines. He is an author of prose and poetry in Esperanto and German, was a co-founder of the German Society for Interlinguistics, and worked as manager, organizer, and editor in national Esperanto associations.

This talk took place on November 10, 2017, at the Graduate Center of City University of New York.

(Author's Note: Please forgive a non-native English speaker for the sometimes inadequat usage of the English language; I would have preferred to deliver this talk in Esperanto.)

Contents:

The Development of a Culture in Esperanto

Blanke's First Classification of Planned Language Projects

Examples for the usage of Esperanto outside of its community

Publishing in Esperanto - as an example of cultural output in Esperanto

2. Publishers from outside the Esperanto movement

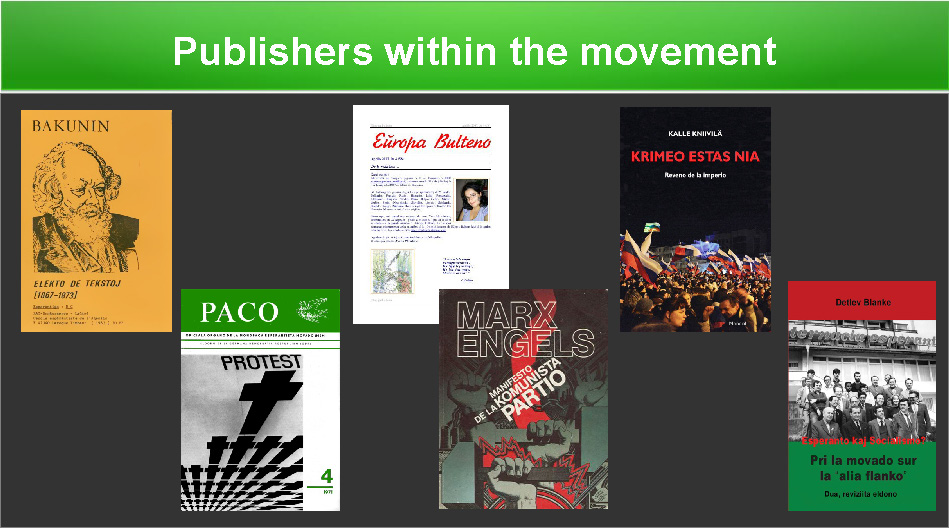

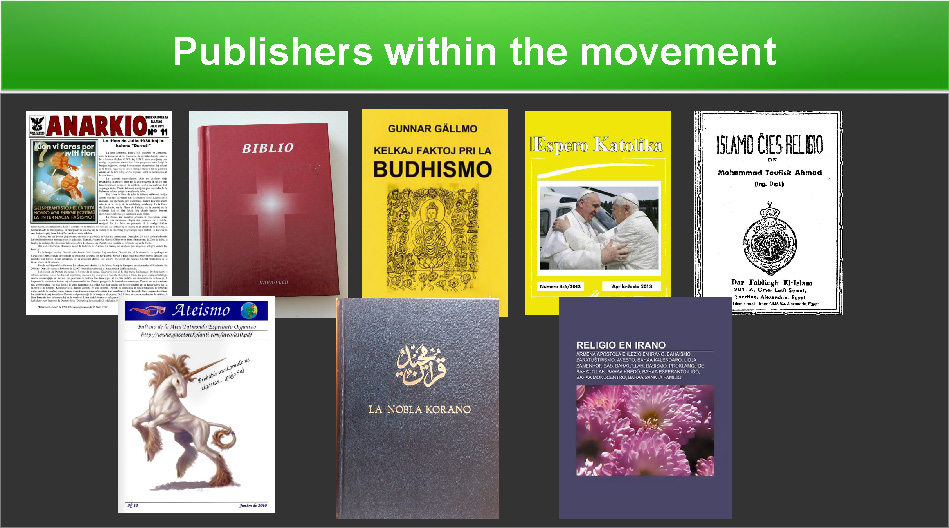

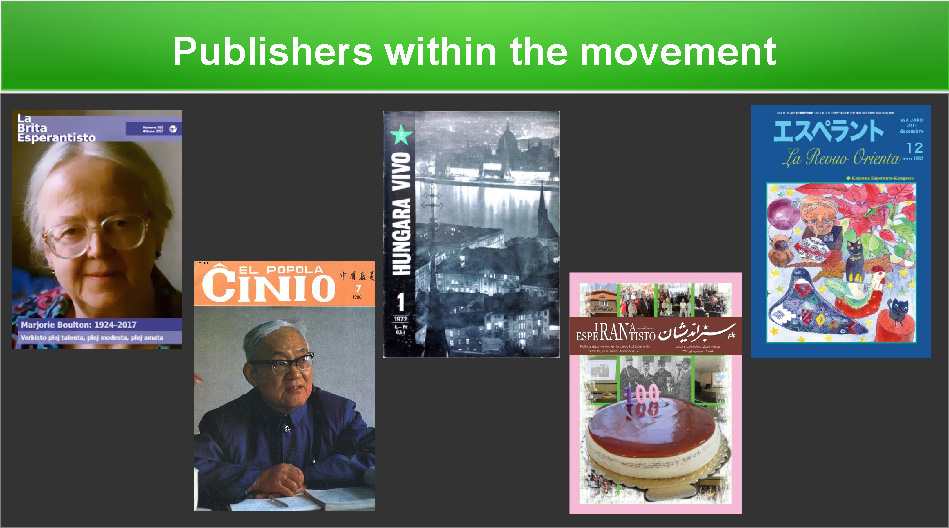

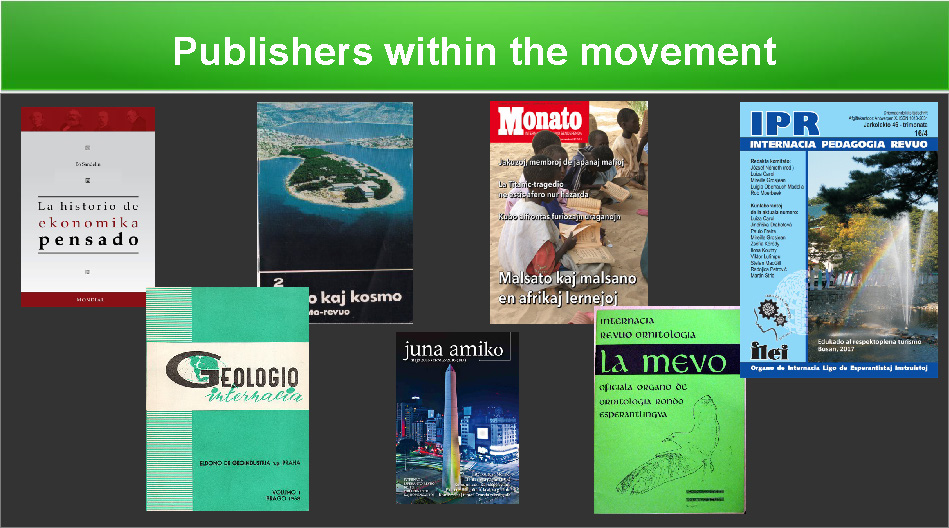

3. Publishers within the Esperanto movement

Introduction

Thank you, everybody, for coming to this last talk of the Tivadar Soros Lecture Series. Thank you to the organizers, and especially to Humphrey Tonkin, who initiated the entire project.

This series started last year with a talk by Esther Schor about the “Endurance of Esperanto” and “how to, or how NOT to plan a language”. Then Michael Gordon described, why Max Talmey, in the 1930s, invented a new language called Gloro: in part to enable better comprehension of Albert Einstein's physics. Our journey then led us to Esperanto propaganda in the Early Soviet Union, presented by Brigid O’Keeffe, and to Ulrich Lins’ talk about the dangerous lives of Esperantists under the regimes of Hitler and Stalin. Finally, last month, we jumped – with Nico Israel – into avant-garde literature and discussed, how James Joyce used Esperanto in his novels Ulysses and Finnegans Wake.

I think it is safe to say that – to those who look closer into the usage of Esperanto in history, politics, literature, linguistics, and especially to those who experience it on a regular, and in many cases on a daily basis – that Esperanto is NOT dead. I am, therefore, glad that with this last talk, we can come full circle and ask ourselves the big question, namely why – in spite of all these facts pointing to a vivid Esperanto history for now 130 years – why the skepticism towards Esperanto and its culture is as strong as it was a century ago.

I started studying Esperanto in 1976, when I was in my last year of high school in East Germany. I became quickly obsessed with the idea and the language, and read one book after another in Esperanto, in order to develop my knowledge of the language and its culture.

Later on, I got more and more involved in the Esperanto movement, leading to my professional work, for a few years, in the headquarters of the East German Esperanto Association and, much later, to founding a publishing company that publishes mainly books in – or related to – Esperanto.

What you see here, is the cover of an issue of Beletra Almanako (Literary Almanac), a literary magazine with three issues every year, between 140 and 180 pages per volume. I have been publishing this magazine since 2007, and its group of editors were – or are –from Spain, Portugal, the US, France, Germany, Italy, and India, and its authors and translators come from all continents. This magazine is the main reason, why I use Esperanto every single day – reading, discussing, arguing, disappointing authors, dealing with vanities, settling disputes, and of course editing and proofreading. I, personally, do not feel a difference between me speaking German or English, or Esperanto – except that my target group is different, depending on the language I use. I speak German to Germans or people who study German, I speak English to my neighbors and to people in the US, and I speak Esperanto to the world. And for me, there is absolutely no difference in the quality of the conversations in these three languages, and I probably speak much more about art and literature and culture nowadays in Esperanto, than I do in English or German.

Now, that is MY experience.

Arguments Contra Esperanto

And it is also my experience to meet a lot of skepticism with regards to Esperanto. Not only are people often surprised that it still exists, but the ignorance about the vitality of Esperanto comes usually along with strong doubts about the linguistic quality of the language and its ability to produce anything of cultural value – in a way that “natural” languages can do this.

That’s a phenomenon accompanying Esperanto from its beginnings until today, and the Esperantists themselves, more often than not, contributed to it. Let me give you some examples, from the early and from modern times – maybe just because it is a lot of fun for an Esperanto speaker to hear that Esperanto is impossible. It’s a bit like in this German sci-fi short story I once read when I was young, where a scientist from Earth meets a scientist from Mars, and in a surprised tone of voice tells him: “I didn’t even know there is life on Mars.”, to which the Martian replied: “Well, I am a scientist myself, and I could easily proof, using scientific arguments, that there cannot be any life on Earth.”

The New York Times wrote, on November 3, 1912:

Herr Zamenhoff’s Esperanto ... had every note of the non-natural from the start. It barred idioms—the most vital thing in all languages—and it offered a worthless substitute for every spontaneous growth. It was easy-going. “Filo” was son, “filino” was daughter (no doubt with due acknowledgements to the Latin group,) and then came “bofilo” for a son-in-law, which none of these would ever have consented to take into the family. How inexpressibly dreary!

Ten years later, on October 8, 1922, the New York Times wrote:

Even an endless chain of interpreters is better than this pallid tongue which has no past, no memories, no rich, terrible and beautiful associations, which has been taught by no mothers and lisped by no babes, which has never been loved and made immortal by the poets, for whose song and meaning and music men have never died and have gone gladly to battle.

Well, that was 1922; and as we heard from Ulrich Lins during his talk here, in May of this year: Just a few years after 1922, many Esperantists did have to die under Hitler and Stalin, only because they spoke Esperanto.

And if you think that the NY Times has changed its attitude towards Esperanto over the years, let me show you something from a few years ago.

In 2014, the New York Times published a special issue of its Magazine about Big “Failures” of humanity. And the authors thought that the best way to emphasize the idea of failure is to translate each chapter's headline into the biggest failure of them all: Esperanto.

Here is what this looked like: “Fiasko” is the Esperanto word for “fiasco” or “failure”.

The chapter “Perdantoj gajnas” (Losers win) deals with failures of financial and economic tricksters.

“La vojo neprenita” (The Road not taken) is about failures in the area of technology.

“Vidi estas kredi” (Seeing is believing) talks about the early failures in virtual reality.

And “Kemia malekvilibro” (Chemical imbalance) is about failures of the pharmaceutical industry.

It’s of course not just the Times. Here is, as just one other example, the headline of an article in the Business Insider, with the usual arguments about a "cultureless" and artificial language:

And the prestigious German Goethe Institute has, on its website, an interview with linguist Jürgen Trabant (Freie Universität Berlin), where he states the following [translation: UB]:

Question: Wouldn't it, for the sake of linguistic justice, be better to introduce an artificial language like Esperanto for the purpose of everyday international communication?

Answer (Jürgen Trabant): I am very much opposed to this idea. From my point of view, at least in the case of Europe, even Latin would be better suited, because behind it, there is a great literature, which Esperanto is lacking completely..."

And then there is the famous quote by philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951): Culture and Value (posthumous, 1980; translation from German: Vermischte Bemerkungen, 1977):

Esperanto. The feeling of disgust we get if we utter an invented word with invented derivative syllables. The word is cold, lacking in associations, and yet it plays at being “language”.

Sometimes it’s hard to understand what’s behind all of this. Is it really just ignorance? There are quite a few examples of opponents of Esperanto, who, after studying it, became surprised fans. So, sure, ignorance is part of it. But there are those, who use arguments and try to explain.

There is for example the interview by linguist Mark Aronoff with Noam Chomsky. Esperanto speakers tend to take this interview a bit too seriously, in my view, because it seems to be based on a more philosophical approach to language than be an analysis of the capabilities of Esperanto. I read it to you, nonetheless:

(Chomsky On Linguistics, Mark Aronoff, Department of Linguistics, Stony Brook University, March 2003)

... nobody can tell you what the rules of Esperanto are. If they could tell you that, they could tell you what the rules of Spanish are, and that turns out to be an extremely hard problem, a hard problem of the sciences, to find out what’s really in the head of a Spanish speaker that enables them to speak and understand and think the way they do. That’s a problem at the edge of science. I mean, a Spanish speaker knows it intuitively, but that doesn’t help. I mean, a desert ant knows how to navigate, but that doesn’t help the insect scientist. [...] We don’t know the answers to the questions of what the principles of Esperanto do because if we did, we would know the answer to how language works, and that’s much harder than knowing how a desert ant navigates, which is hard enough. So, now it is understood that Esperanto is not a language. It’s just parasitic on other languages. Then comes a question, which is not a linguistic question, but a question of practical utility. Is it more efficient to teach people a system which is parasitic on actual languages, and somewhat simplifies, eliminating some of the details of actual historical languages; or is it just more efficient to have then a whole lot of languages?

And here is a good example, in terms of argumentation against the cultural value of Esperanto, which I found on mezzoguild.com. The author, Donovan Nagel, is an expert in Applied Linguistics, and tries to focus on the aspect of culture – by writing:

Not only does Esperanto have no culture but its adherents are delusional. ... Esperanto has no country or geographical ties to an ancestral homeland. Unlike natural languages, you don’t learn Esperanto because you’re fascinated by a country, people group or location.

Outside of a few crackpots who decided to turn their kids into circus acts by raising them with Esperanto as a first language, it has no intergenerational identity or national/tribal history.

It’s therefore the same as any other conlang [that’s short for “constructed language” – UB] in this regard. But… Esperantists always and predictably fire back with:

“You’re wrong. We do have a culture. We have Esperanto music, food, events, literature… etc.”To which I reply that this shows an incredibly shallow and poor understanding of what culture actually is. It’s exactly this kind of ignorant interpretation of the term ‘culture’ that I denounce in almost everything I do and write.

And it’s not just me:

“…culture is defined as the shared patterns of behaviors and interactions, cognitive constructs, and affective understanding that are learned through a process of socialization. These shared patterns identify the members of a culture group while also distinguishing those of another group.”

“Most social scientists today view culture as consisting primarily of the symbolic, ideational, and intangible aspects of human societies… The essence of a culture is not its artifacts, tools, or other tangible cultural elements but how the members of the group interpret, use, and perceive them.” [web pages of the University of Minnesota’s Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition.]

And he went on to say that...

Culture is a deep and multi-layered phenomenon.

To limit it to things like music, performances, literature, and cuisine is insanely ignorant and unfortunately indicative of how a lot of modern progressives treat culture even outside the Esperanto community.

Or like a friend of mine tried to explain to me:

After the inventor of a new language went through all the trouble putting together hundreds of grammatical rules and creating tens of thousand of words, it seems like a much easier task for him to translate a story or book into this new language. But does this mean that – because of this book – this new language has now a culture?

Arguments Pro Esperanto:

Well, enough complaining. What is the OTHER side saying? Let’s look at these issues from inside the language and movement and establish a few facts.

Let’s start with a short quote by E. James Lieberman, a psychiatrist and former professor at the George Washington University (2015, www.researchgate.net):

Esperanto has a culture, though no nation or "people" except those who choose it. ... Its culture is unique--starting around 1890--through cross-cultural activity. The literature is extensive, with translations of many works by native speakers of the original (unlike most translations). [It is a rule in the translation industry, that translators translate usually into their native language. This is not possible in Esperanto. - UB]... My understanding of language in general, including my native English and college German, has benefited from Esperanto...

This gives us a first clue into what Esperanto culture, maybe, really is: “cross-cultural activity”.

And since wiser people than I can explain this much better, I want to follow up with a second quote, this time by Pierre Janton, a Frenchmen, who was a philologist and professor at the University of Clermont-Ferrand, from his book: Esperanto – Language, Literature, and Community (translated into English by Humphrey Tonkin, Jane Edwards, Karen Johnson-Weiner; edited by Humphrey Tonkin):

In Chapter 4: Expression, he writes:

Also the growing number of users of Esperanto across the world, — with their various linguistic traditions, — has subjected the structural cohesion of the language — to considerable strain, — but [...] Esperanto has proven to be flexible, plastic, and, in a word, international. These decisive tests have brought it successfully from the experimental stage to its current self-sustaining condition. Exploiting the potential contained in the Fundamento [the basic book of rules of Esperanto – UB], modern usage is not limited to the usage employed by Zamenhof. On his original foundation new structures have been built [...] Like any other linguistic system, Esperanto now functions independently, in accordance with its own rules and not on the basis of decisions by outside agencies. Zamenhof created a project, but the Esperanto community has made it a language—a phenomenon unique in the history of language.

Well, anybody who has been swimming long enough in this Esperanto sea that connects the territories of the many national and regional cultures, will be able to confirm that.

Esperanto is a language that has a history of 5 or 6 generations, and people speaking it are spread on all the continents where people live. The basic cultural element can - perhaps - be defined as a strong "internal idea" – i.e. the will to achieve justice among all peoples, cultures, and languages. On this basic principle, the rest of the culture is built. Yes, Esperanto has of course a huge literature, both original and translated. There are really too many valuable books to read in a lifetime, and the number is still growing fast. You can enjoy music in Esperanto, original songs or songs coming from many countries. With the growth of the Internet in these past few decades, Esperanto has experienced a cultural boom that was unthinkable at the time at which I started to become active in the movement: Websites and blogs, groups and forums, online learning, excellent online dictionaries, online magazines of all sorts – in short, you can find a flourishing Esperanto culture on the web alone. Just search for the term “Esperanto” in YouTube and surprise yourself.

The Swiss linguist, psychologist and author Claude Piron, in his article An interesting case of bona fide prejudice tries to counter the argument that Esperanto...

"... lacks the richness and vibrancy of a living language."

[or, if I may repeat what we heard Noam Chomsky say: ... that Esperanto is "... just parasitic on other languages.... and somewhat simplifies, – eliminating some of the details of actual historical languages"]

In his article, Claude Piron writes:

[...] A simple analysis of literary texts shows how invalid such a criticism is. Esperanto is a rich language because nothing restricts the linguistic creativeness of the speaker or writer. Let's consider the following sentences from a novel [...]:

Ĉu kun la aliloĝiĝo oni alipsikiĝas?

'When one moves from one address to another does one also move from one psyche to a new one?'Ŝi senŝvitigadis la frunton per la rando de sia sario.

'She was constantly removing the perspiration from her forehead with the border of her sari'.

Claude Piron continues:

It is unfortunate that the reader who doesn't understand Esperanto won't feel the evocative power of the many untranslatable words appearing in those sentences. Not only is it impossible to give an accurate translation, but it is difficult even to transmit their meaning, which is obvious to anybody who's learned Esperanto.

In the first sentence, ali-loĝ-iĝ-o [...] is analyzed as

ali — 'other',

loĝ — 'lodging',

iĝ, — a morpheme with a vast semantic field including concepts such as 'becoming', 'changing', 'being switched to',

-o — a marker indicating that the word is used as a noun.The word alipsikiĝi 'to change one's psyche' follows the same pattern: ali-psik-iĝi (the final -i means that the word is used as an infinitive; ...).

What canNOT be communicated is the vibrancy of the word. The echo in the reader's mind and heart of such a word is quite different from a literal, flat [back-]translation of [English] 'changing one's psyche' which would be ‘ŝanĝi la psikon’ [...].

In the second sentence, the word sen-ŝvit-ig-ad-is is analyzed as

sen — 'without',

ŝvit — 'sweat', 'perspiration',

ig — 'make such and such', 'cause something or someone to. . .',

ad — repetition or imperfective aspect,

-is — verbal function in the past tense.

A literal translation would be 'repeatedly she rendered [her forehead] perspirationless'. Such a word may appear long and barbaric to a non-initiate. However, experience proves that little practice is needed for eye and brain to perceive the elements that make up such words and to make automatically, unconsciously, the synthesis that delivers the meaning. Senŝvitigi 'to make perspirationless' is part of a well known series [in Esperanto] that comprises sen-arb-igi to 'clear of trees', 'to deforest', sen-kolor-igi 'to discolor', sen-vest-igi 'to undress', sen-kulp-igi 'to excuse', 'to exonerate', sen-hered-igi 'to disinherit', etc. Such series are infinite.

Anybody who knows both Esperanto and English and compares the above sentences with their translation immediately feels that English cannot render the impact, the resonance, the connotations of the Esperanto words. This does not mean that English is poor, but that its richness is different. That Esperanto doesn't lack richness and vibrancy is a verifiable fact.

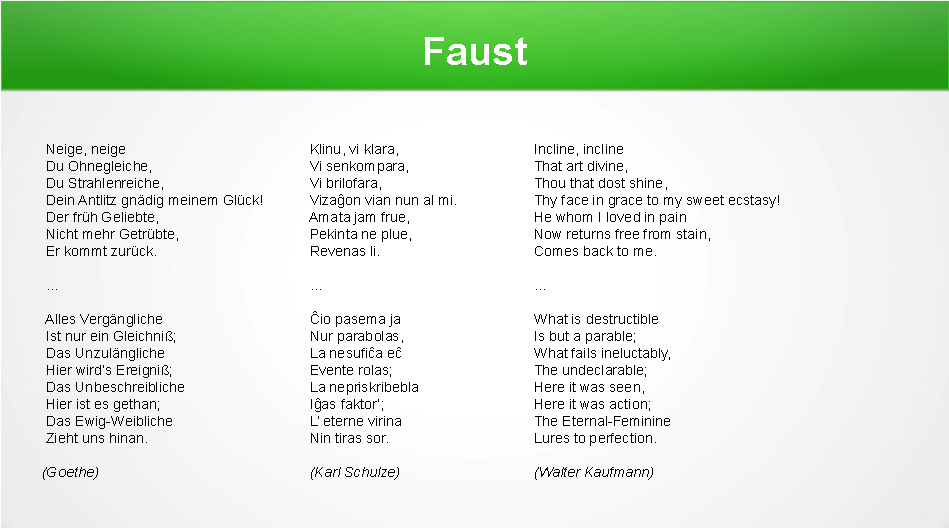

That reminds me of an experience I had a few years after moving to the US. I had just published the entire “Faust” by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, in an excellent Esperanto translation by the German Karl Schulze. As a German, especially if you went through German high school and college, you are usually quite familiar with this piece and know many lines by heart. I was amazed, how well Schulze was able to reproduce not only the content, line by line, but even rhythm, rhyme, and feeling of the original. Some of the most powerful lines of this piece gave me the same goose bumps in Esperanto as they did in German. And I became curious about English translations. The best I could find is the incomplete translation by Walter Kaufmann.

See here, for example, the very simple, philosophical verses at the very end of part 2 in German, Esperanto and English.

If you speak German and English – or Esperanto and English, you will see the many instances where even Kaufmann had to deviate from the German word choice, rhyme, and/or rhythm. The Esperanto translation had to take a poetic license only in the 4th verse. In addition, the Esperanto version is as powerfully simple as the German, whereas the English seems to me a bit constructed and forced – but I am not native English and might be wrong.

The Development of a Culture in Esperanto

Now, let’s get back to Donovan Nagel, who claims that Esperanto is just “the same as any other conlang”. He gave his article the title “Why I won’t learn Esperanto”. This indicates that he has not looked deeper into the language, and probably also not into any other constructed language, which, of course, makes it easy to claim that they are all in the same cultureless category.

My former boss at the East German Esperanto Association, the linguist Detlev Blanke, in his books and essays (i.a. “Internationale Plansprachen” [international planned languages]), started creating a system of linguistic, cultural, and social categories, that helped him not only organize the existing constructed languages, but which provides at the same time – and most importantly – an argumentation proving the steady development of culture among the active users of Esperanto, i.e. within the Esperanto movement or Esperanto community.

As many of you know, there are more than 1000 artificial language projects, and almost every year, a new one is being invented. Blanke could show that the life of more than 900 of these projects ended immediately at the first level of his system of categories.

Blanke's first version of a classification of planned language projects:

(1) Publication of the structure of the new language project.

In many other cases, there followed a more or less short

(2) Production of texts (newsletters etc.),

In many other cases, the authors of the projects succeeded in finding a few interested people from different countries who learned the system and used it, mainly for limited

(3) International correspondence.

A few of the many projects were able reach the next level: a certain

(4) Organization of the adepts and a somewhat systematic Publicity.

Blanke called the language projects covered by these steps 1-4: “Planned language projects”. They include almost all of the existing artificial languages and remained on the level of a "project".

If a language developed beyond step 4, it became, as per the terminology used by Blanke, a “Planned semi-language ”. Adepts of the languages in this category were able to

(5) create a limited body of literature,

(6) publish small journals

(7) create specialized texts

(8) teach their language project to a certain extent

(9) speak it internationally, to a certain extent.

Languages in this category are, e.g., Ido and Interlingua until today, Occidental-Interlingue in the past century, and, up to the end of the 19th Century, Volapük.

Only Esperanto went further, up to the levels of category 3, and therefore, so Blanke, it is the only Planned language:

Category 3 includes:

(10) further specialized practical usage (specialized journals and organizations),

(11) a developed network of national and international organizations,

(12) a wide range of literature,

(13) relatively wide instruction (sometimes state-supported),

(14) large periodically occurring international events,

(15) regular radio-programs,

(16) clear social and political distinctions in the language community

(17) an independent youth movement,

(18) a certain evolution of independent cultural elements linked to the language community,

(19) bilingualism (involving an ethnic and a planned language) of children in (most often international) families.

Blanke adds, that “all three groups merit the interest of linguists. A consequence of this classification, if followed very rigorously, is that it is not possible to speak in the plural of planned languages but only of planned language systems and one planned language.

In a later version, Blanke developed this set of categories even further and came up with a total of 28 levels. Among the additional levels are the role of the language in electronic media, the emergence of elements of an original culture and the factor of language development, among others, all of which apply only to Esperanto:

28 stages of development of language, community, and culture:

Blanke's Complete Classification of Planned Language projects

The list below is a translation from German (summarized and with a few added comments) by me. For the German original, see: Blanke, Detlev. 2000. Vom Entwurf zur Sprache. Klaus Schubert, ed. Planned Languages: From Concept to Reality. Interface: Journal of Applied Linguistics 15/1:37–89.

(1) Manuscript (i.e. the language project exists in writing)

(2) Publication (in form of a brochure or book)

(3) Teaching Material (small dictionaries, grammars, sample texts)

(4) Publicity / Advertisment (of the new language project)

(5) Periodical (usually one, for the small group of adepts)

(6) Correspondence (this is the actual beginning of practicing the language)

(7) Translations and Original Texts (a first, small number of brochures and books besides teaching material)

(8) Oral Communication (this does not usually happen on levels 1 to 7; it happens only when two or more adepts meet for the first time)

(9) Small Organisations of Adepts (local, regional or first international clubs or small associations of adepts)

(10) Increase of Text Production (larger amount of periodicals and books; this step results in the development of a few text genres)

(11) Language Courses (private teachers and students)

(12) Small Language Community (i.e. the feeling of belonging to a community; the slowly developing need for more direct and indirect contacts, for a more varied offer of national and international periodicals, covering a broader range of topics)

(13) Discussion of Linguistic Problems (discussions about the correct use of the language and the need for new words; maybe discussion of language reforms...)

(14) Communication among Experts in Specialty Fields (first professional communications; maybe first specialty magazines)

(15) Events (first organized regional, national, and international meetings, with an increasing number of participants)

(16) Differenciation of the Structure of the Language Community (local, regional, national, international organisations on different topics; development of tourism; book distribution networks; training of language teachers...)

(17) Development, Stabilisation, and Codification of Language Norms (Development of written and oral language styles; development of literary styles and of terminologies in various specialty and professional fields; monolingual dictionaries; specialty dictionaries)

(18) Big, worldwide events (annual world conferences with hundreds or thousands of participants, with cultural, linguistic, and administrative/organizational agenda items)

(19) Worldwide Dissemination (teaching materials and dictionaries for more and more ethnic languages, in better and better quality; the language has speakers on all continents)

(20) Interlinguistics (the developing need of scientific research in the field of the planned language, its usage, community, and history; an increasing number of studies about the language, its literature, its terminology development; some colleges outside the movement become interested in the area of interlinguistics; some of the interlinguistic production is registered in general linguistic bibliographies)

(21) Heuristic Effect (linguists and scientists outside the language community become interested in the idea of an international language and start experiments using this idea or the language itself for projects outside the language movement [in the case of Esperanto, this happened, e.g., in the field of general Terminology Science at the time of Eugen Wüster, or with an early automated translation system called DLT that used Esperanto as intermediate language between source and target languages)

(22) External Usage of the Language (i.e. organisations, companies, and institutions outside the movement start using the language for their own purposes; e.g. for the purpose of information [governmental information promoting the country internationally] or advertisment [e.g. "Movado", see below]; also, global companies like Google, Facebook, Wikipedia, and others, offer their user interfaces in the new language - UB)

(23) Schools and Universities (...start offering courses in the language; that includes the academic education and training of university teachers for this purpose)

(24) Electronic Media (the language has an increasing presence first on radio and TV, on video, CD, and DVD, and nowadays on the Internet [in the form of thousands of apps, in countless web applications, and on millions of websites (including blogs)... - UB])

(25) Social Differenciation (strong differenciation with regards to religions, politics, philosophies, ideologies; incl. age-related differencation with youth organisations and regional and international youth events etc.)

(26) Family Language (marriages of two speakers of the language make it the first language of the family, and the first language of the children)

(27) Original Culture (development of a history of the community's culture with its traditions, ideals, myths, identifiers [flag, anthem, other songs], theater productions, description of the history of literature in the language...)

(28) Further Language Development (the expressiveness of the language develops fast, incl.: phraseologism, polysemism, synonyms, also functional styles developed directly by the day-by-day usage of the language [often untranslatable phrases or words or acronyms]; specialty-"speak" in all imaginable areas, from fiction and poetry to journalism to professional usage, administration etc.; recognizable styles of authors; slang of youths; all this with unifying factors at the same time: standardizing dictionaries, refined description of the grammar, language-related decisions by linguistic institutions of the community, etc. -- The result is a constant, creative battle between a standardization process on the one hand and, on the other hand, a free and unshackled usage of the language in more and more areas. - UB)

Needless to say that only Esperanto went through all of these 28 steps. Most other projects stop at level 4 or earlier; a handful of planned language projects reached levels 15 or 16, or went just a bit further. Some language projects have a small, constant presence on the Internet [level 24].

It was this constant spread and development that Pierre Janton (see above) meant, when he wrote that “Esperanto now functions independently, in accordance with its own rules ... Zamenhof created a project, but the Esperanto community has made it a language.”

And the very definition of "Culture" that Mr. Donovan, above, had used as an argument against Esperanto (“…culture is defined as the shared patterns of behaviors and interactions, cognitive constructs, and affective understanding that are learned through a process of socialization. These shared patterns identify the members of a culture group while also distinguishing those of another group.”) seems to describe in two sentences what the Esperanto language and community went through over the past 130+ years.

Examples for the usage of Esperanto outside of its community

Not only, as we just heard, is Esperanto in a much higher category, in comparison with all the rest of the constructed languages, but unlike those, it has become, over time, part of the general memory of human mankind. People use it in other contexts. Here are just a few phrases I found in various recent news outlets in the past weeks, and you have certainly heard similar comparisons yourself.

- Entertainment is the Esperanto of our age, a universal language...

- The scope of music is immense and infinite. It is the ‘esperanto’ of the world. (Duke Ellington)

- The movie’s real idiom is the Esperanto of violence...

- Fried bread is the Esperanto of the kitchen, an international language of hot oil and dough that’s spoken around the world.

- Golf is the Esperanto of sport. All over the world golfers talk the same language...

- Body language is the Esperanto of basketball, and both Stateside and in Athens people didn't like what they saw.

- Electricity is the Esperanto of energy.

- Oil is the Esperanto of the world’s fossil fuels, speaking the same language everywhere.

- Bacon is the Esperanto of ingredients. It speaks to every recipe.

- And yodeling is the Esperanto of the Universe.

I leave it up to you to decide if these comparisons or metaphores make any sense.

But the notion or idea of Esperanto has been used by the outside world in far more detail than just as a metaphor in newspaper articles.

Mainstream movies, for example, have used Esperanto in one way or another. Wikipedia has a long list of them, from 1924 to our days. Let me only mention three:

In 1924, the movie The Last Laugh was directed by F.W. Murnau and had street signs, posters, and shop signs written in Esperanto). In 2016, the movie Captain Fantastic, had a scene, in which two girls speak fluently Esperanto during a bus ride).

The most famous of these films is maybe The Great Dictator by Charlie Chaplin, who decided to have the signs in the shop windows of the Jewish population in the Ghetto written in Esperanto, instead of German.

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Esperanto-language_films)

And then, there is of course the infamous science fiction movie Incubus, a black-and-white horror movie from 1965 staring William Shatner, in which all actors speak entirely in Esperanto. It is an awful movie.

The same outside usage of Esperanto can be found in literature all over the world.

Last month, during our lecture series, we heard in detail about Esperanto in Ulysses and Finnegans Wake, but again, you can rely on the fan writers of Wikipedia, who put together a long list. Let me just mention again 3 famous examples:

Esperanto has been cited as the inspiration for George Orwell's Newspeak in “1984”. Orwell had been exposed to Esperanto in 1927 when living in Paris with his aunt Nellie Limouzin, who was then living with Eugène Lanti, a prominent Esperantist.

The Stainless Steel Rat novels by Harry Harrison (who was an Esperanto speaker and included contact details for the British Esperanto Society in his books). He often described a future where Esperanto is spoken.

And

in the novel The House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende, Esperanto is believed by Clara the Clairvoyant to be the language of the spirit world along with Spanish.

Last, but not least, I just want to mention that Esperanto has also been used in advertising. Not only have product names sometimes Esperanto names, but Esperanto has also directly been used in advertisement texts, especially in the 20s and 30s, and again in the 50s and 60s of the past century. The most famous brand using an Esperanto word as company and product name until today, is probably the watchmaker Movado (the word "movado" means, in Esperanto, "a constant motion").

Publishing in Esperanto - as an example of cultural output in Esperanto

Now, let’s look at the cultural output of the Esperanto movement itself.

Given the fact that “Esperanto-Land” is not a big region or city, where a people lives together, but a diaspora of people living spread across the world, the forms of cultural activity take very specific shapes. If you want to hear a life concert of Esperanto singers, or see a life theater piece in Esperanto, you can’t just go to your local theater, but you must travel, sometimes far, to very large Esperanto events. I saw my first theater performances in 1987 during the World Esperanto Conference in Warsaw, where close to 6000 people were in attendance. I saw there, in Esperanto, “The Cave of Salamanca” by Miguel de Cervantes, and “Picnic on the Battlefield” by Fernando Arrabal.

There are every year hundreds, maybe thousands of small local and large regional and international Esperanto events, specialty events like meetings of certain professionals, youth gatherings, music festivals, international New Year celebrations, and so on, and most of them include a lot of cultural events and activities.

Let’s take a closer look at the area, where I am most active: the publishing of books in Esperanto.

It is said that more than 25.000 titles have been published in Esperanto over the lifetime of the language. This might seem very little – or very much, depending on which ethnic language and literature you are comparing it to.

Who is publishing in Esperanto?

- Individuals /

- Publishers from outside the movement

- Publishers within the Esperanto movement

1. Individuals as publishers

Esperanto began in 1887 as an endeavor by an individual, the multilingual ophthalmologist, Dr. Ludwig Zamenhof, and he had to publish the very first books, introducing Esperanto, by himself.

Also La Esperantisto (The Esperantist), the first Esperanto magazine, was published by Zamenhof himself, but financially supported by an early German speaker of Esperanto.

Throughout the history of Esperanto, individuals have played an important role in financing publications. Mostly “idealistic and philanthropic people dedicated their time and money” to Esperanto, especially in the area of publishing, in these early years.

Another very early Esperanto review, La Mondlingvisto (The World Linguist) was founded and financed in 1889 by the president of the Esperanto Club in Sofia, Bulgaria.

The “Esperanto Encyclopedia” – Enciklopedio de Esperanto – published first in 1933, tells the not atypical story and adventure of one of the early monthly magazines, Lingvo Internacia (International Language) and the role individuals played in its publication [summary – UB]:

Valdemar Langlet, a Swedish university student, visited the Russian chemist Vladimir Gernet in Odessa at the Black Sea in 1895. Since Zamenhof’s magazine La Esperantisto had just been discontinued, Langlet and Gernet discussed the urgent need for a new international magazine, and decided that the Esperanto Club of Uppsala, Sweden, would publish Lingvo Internacia, with Gernet in Odessa as chief editor and director of finances. Now, this was 100 years before the Internet. At first, print proofs were sent by snail mail from Sweden to the Black Sea for correction, then sent back for printing in Sweden – a process that caused many delays. The first regular issue with 16 pages appeared in 1896, and already in 1897, the vice-president of the Esperanto Club of Uppsala, Finland, took over the editing, to avoid these delays – until the end of 1898, when the club ran out of money. In the second half of 1899, a wealthy Swedish Esperanto fan decided to finance it, and in 1900, a new and energetic printer was found in Hungary: the Esperantist Paul Lengyel, who then became editor of the magazine. When Lengyel moved to Paris in 1904, he took the magazine with him and published it with the help of a group of French Esperantists until its demise at the beginning of the First World War. It seems little short of a miracle that the magazine lived through 252 issues and a total of 6,574 pages.

Individuals have published in Esperanto throughout its history, and this phenomenon has gained new impetus nowadays, from the ever-increasing self-publishing activities that developed in ethnic languages and in Esperanto and a few other planned languages projects with the growth of the Internet.

2. Publishers from outside the Esperanto movement

Every now and then, Esperantists could convince publishers from outside the Esperanto movement to publish books in or about Esperanto, but in many cases, the publishers recognized more or less quickly, that there is not much money to be made in the market of Esperanto enthusiasts, and the cooperation stopped.

Zamenhof himself published his first textbooks and literary translations with a printer and publisher in Warsaw, Kelter. Later, when the center of the young Esperanto community moved to Nuremberg in Germany, a company there, W. Tümmel, became the center of publishing for the new language.

The first larger commercial publisher to take an interest in Esperanto, Hachette, was one of the best-known French publishing companies in 1901, when the scientist and Esperanto adept Carlo Bourlet persuaded it to publish books and magazines for the Esperanto market. The activists of the early Esperanto movement understood this as a unique chance, since Hachette had branches and correspondents in many countries and its books were easily accessible almost anywhere. On the basis of a contract between Hachette and Zamenhof, the publishing company launched a book series with works of Zamenhof and others, including one of the most reputable Esperanto journals of the time, La Revuo (The Revue). Zamenhof’s contract in 1901 with Hachette et Cie. had a big influence on the development of publishing in Esperanto. Hachette published works of Zamenhof, two book collections: the Kolekto Aprobita (The Book Collection approved by Dr. Zamenhof) and Kolekto de la Revuo (the La Revuo collection). Hachette closed its Esperanto department in 1918, selling its existing stock of books in Esperanto and its rights to new publications.

Ferdinand Hirt und Sohn was a well established German company based in Leipzig, mainly involved in textbook publishing for schools. After publishing Esperanto textbooks (1919-1921), it opened an entire Esperanto department and also published prose, textbooks, dictionaries and other non-fiction, including works by Zamenhof, by the Swiss Esperanto journalist and historian Edmond Privat, and Eugen Wüster’s Enciklopedia Vortaro (Encyclopedic dictionary). This stopped with World War 2.

The renaissance of Esperanto after the the second world war began relatively slowly and, ironically, received more momentum only with the deepening of the cold war – which lasted until the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989/90.

In East Germany (German Democratic Republic), for example, books by Bertolt Brecht, Heinrich Böll and others were translated, then published at the state-run publishing house Edition Leipzig, who sold them internationally. Another East German publisher, Verlag Enzyklopädie Leipzig, published Esperanto dictionaries and linguistic studies; and materials for language courses were produced by the not-for-profit organization Kulturbund or by academic publishers like the East German publisher Akademie-Verlag.

Similar activities with Esperanto publications by state-run publishers could be seen in other Eastern European countries during the cold war, especially in the Soviet Union.

Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland and Bulgaria were able to register and run their national Esperanto associations as publishing houses. In China, a separate state-run Esperanto publishing company was founded, which published books and magazines for a very long time.

In many instances, national publishing companies of the so-called socialist countries translated and published Esperanto tourist materials or propaganda material about their countries or about socialist ideology.

Some western European publishers outside of the Esperanto movement also published books, but there, in general, publishing in Esperanto remained mostly a result of individual initiative – with some exceptions.

Bleicher Verlag, a west German publisher with large fiction and non-fiction lists, published a few books in Esperanto in the 1980’s, mainly because the owner of the company was a friend of Esperantists.

However, linguistic publishers, e.g. of dictionaries or textbooks for the study of the language, continue to include Esperanto in their book programs.

To give one typical example: The well-known Verlag Langenscheidt in Germany, who bought the East German publisher Verlag Enzyklopädie Leipzig and it’s Esperanto dictionaries after the unification of Germany, published later an extensive German-Esperanto dictionary on the condition that the German Esperanto Association buy part of the print run. When the dictionary did not sell as many copies as Langenscheidt had hoped, they declined to produce other books, including the reverse version, which was nonetheless published in 1999 by another German publisher of dictionaries, Buske.

Esperanto materials for English speakers were, for example, published by English Universities Press as part of the Teach Yourself Series. There are many other examples all over the world. And there are certainly other reasons, why private publishing companies include a few Esperanto books in their program. The most active publishers, however, are all based within the Esperanto community itself.

3. Publishers within the Esperanto movement

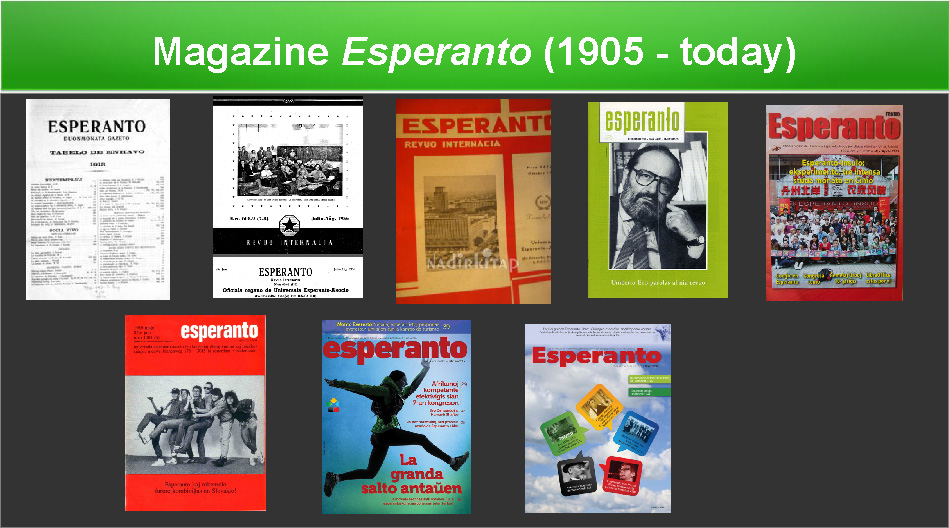

In 1905, the magazine Esperanto was founded. From 1908 to our days, it has been the official organ of UEA (Universal Esperanto Association), and is by far the most enduring periodical published in Esperanto.

Presa Esperantista Societo (Esperanto press society) was founded in 1904 in Paris, as competition to the Esperanto department at Hachette. Publishing books with a focus on a pure, conservative Esperanto, avoiding neologisms and modernisms in the structure and grammar of the language, it was the first important publishing company developed within the Esperanto movement, by a group of ardent disciples of Esperanto. It accused Hachette of monopolizing the Esperanto book market, but, like Hachette’s Esperanto department, it ceased to exist after the First World War.

Publishing within Esperanto received many boosts between the two world wars, especially because of the social and political developments in Europe and the continuing dissemination of Esperanto throughout the world. Of the four publishers with the biggest influence during this period, three were initiated by Esperantists, reflecting the cultural and social life of Europe in the 1920’s and 1930’s.

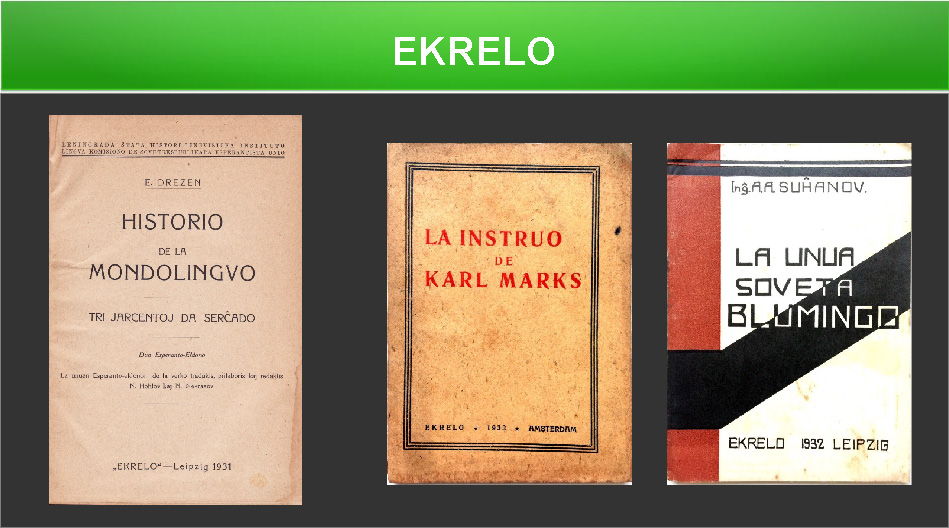

Eldon-Kooperativo por Revolucia Esperanto-Literaturo (EKRELO; Publishing cooperative for revolutionary Esperanto literature) was a unique phenomenon on the Esperanto book market, or – as Esperanto en Perspektivo calls it – a “mysterious publishing company” (Lapenna, Lins and Carlevaro 1974:48). Yet its existence reflected the political situation in Europe more than any other Esperanto organization.

EKRELO was founded in 1930 in Leipzig as an “independent international Esperanto publishing company” with “close relations to the Union of Esperantists of the Soviet Republics (Sovjetrespublikara Esperantista Unio, SEU) (Kökeny & Bleier 1933:117). After Hitler came to power in Germany, in 1933, EKRELO moved to Amsterdam. It published political brochures, for example on the building of socialism in the Soviet Union, but also novels, textbooks and linguistic studies, more than 60 book titles all together. Because of the political developments in Europe in the first half of the 1930’s it could not, however, complete its most ambitious project, an Esperanto version of the selected works by Lenin in 16 volumes.

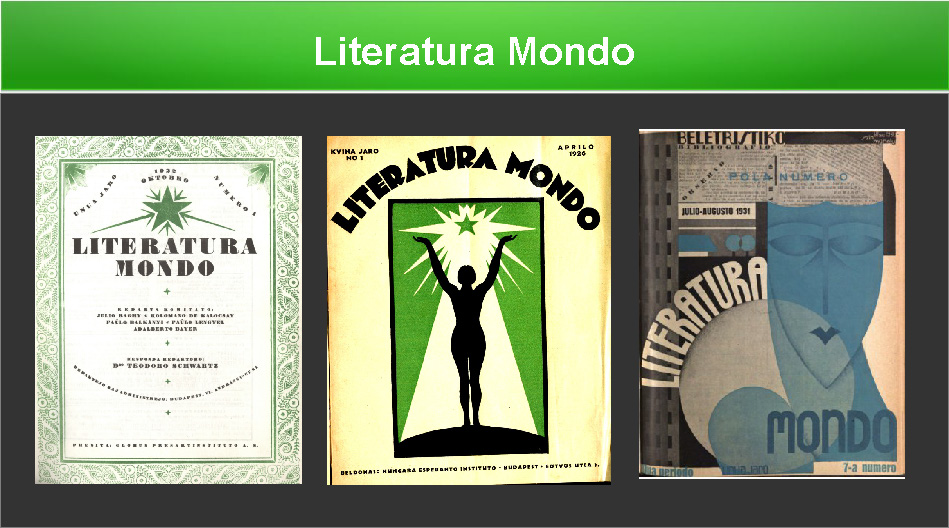

Literatura Mondo, a publisher of a magazine of the same name, was also a highly reputed book publisher. Among its publications were works on the language itself, but also a large number of original and translated books with poetry and prose. Under the leadership of the poet Kálmán Kalocsay, it became the center for a circle of writers belonging to what was known, in the 1950’s, as the Budapest School, the cradle of modern Esperanto literature.

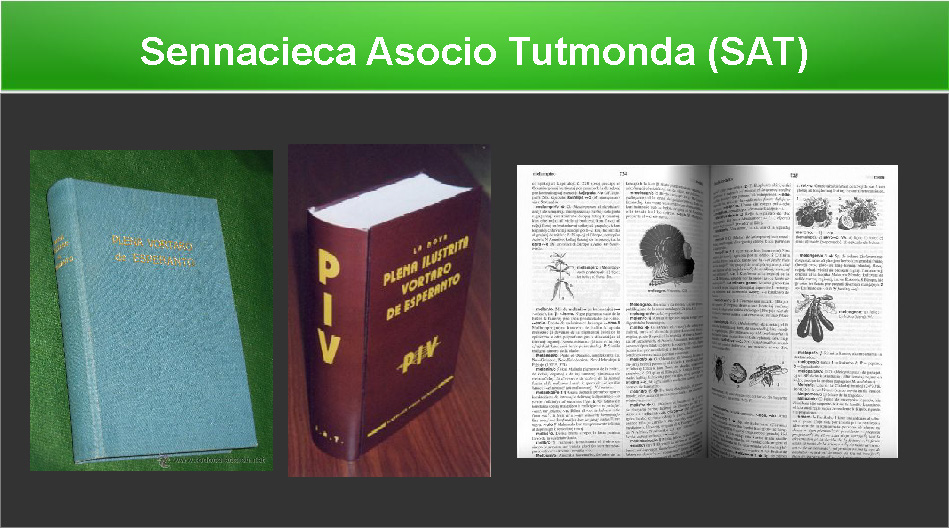

Sennacieca Asocio Tutmonda (SAT) was and is an international association (founded in 1921) whose members are based in the working class, and others, who did not want to accept the political neutrality of the Universal Esperanto Association, UEA. Over the years, SAT has published many political and literary works, but its greatest publishing achievement (and one of the most influential Esperanto books of all times) is the authoritative monolingual dictionary in Esperanto, the Plena Vortaro de Esperanto (Complete dictionary of Esperanto;1930), later Plena Ilustrita Vortaro de Esperanto (Complete illustrated dictionary of Esperanto; 1970), and currently, Nova Plena Ilustrita Vortaro de Esperanto (New complete illustrated dictionary of Esperanto; 2002).

From the second world war on, especially from the 1950's to the end of the 1980s, until today, the number of publishers in Esperanto expanded enormously, and it would be impossible to discuss them all in detail here. However, it is interesting to note that they mirrored the political, social and cultural outside world and the societies, in which they were embedded:

There are political publishers, mainly on the left. There was propaganda material in Esperanto on both sides of the iron curtain, but it might not be surprising that the output in the Eastern block, including Soviet Union and China, outweighed the efforts by Western European countries.

Since there are religious and atheist Esperanto organizations, there were and are also many religious (and atheist) publications of all sorts.

There are national Esperanto associations in approx. 100 nations, and many of them, but also many local clubs or regional associations, published or publish newsletters or magazines of varying quality.

There are social, generational, philosophical, linguistic, historical, scientific, professional and many other kinds of international Esperanto associations, and most of them publish not only periodicals in Esperanto, but also serious books, in the fields of their expertise, like translations from national languages into Esperanto, or books written by professionals or journalists (sometimes well-known on a national level) originally in Esperanto for an Esperanto readership.

Many publishers, over the history of the language, had a very short life, but an increasing number achieved stability. The World Esperanto Association, UEA, remains the most productive publisher to date, but in the last fifty years there have been other outstanding companies and publishing associations, like Flandra Esperanto-Ligo, Ĉina Esperanto-Eldonejo and Sennacieca Asocio Tutmonda, but also Japana Esperanto-Instituto (Japanese Esperanto Institute), Sezonoj in Russia (Seasons), Fonto in Brazil (Source), Pro Esperanto in Austria, Mondial in New York, and others. The two publishers making the biggest contribution to the earlier post-war Esperanto movement in terms of linguistic and literary quality and quantity of published books were:

Stafeto (Courier), which was run by publisher Juan Régulo Pérez in La Laguna, Spain, from 1952 to 1975 and published 93 books; and

Hungara Esperanto-Asocio (Hungarian Esperanto Association), who published 114 titles from the 1960’s to 1990.

Both of these publisher left also an impressive number of titles behind that have become literary classics in Esperanto.

4. A note about Electronic publications

Given the ever-increasing number of Esperanto content on the Internet and on apps for smartphones and tablets, and of eBooks for eReaders, it has become impossible to give an overview of the publishers and to clearly identify, which are serious publications and which are amateurish. Let me just add that in the past few years, much later than the outside book world, more and more professional Esperanto publishers understand the advantages of eBooks, and many serious books are now being published simultaneously as print and eBook versions. eBooks make a lot of sense for a market, whose readership is spread throughout the world. (Cf. Esperanto books on Smashwords or on Google Play Books.)

Among the many thousands of Esperanto-related initiatives on the web (and the millions of web pages treating Esperanto as topic), let me just mention three:

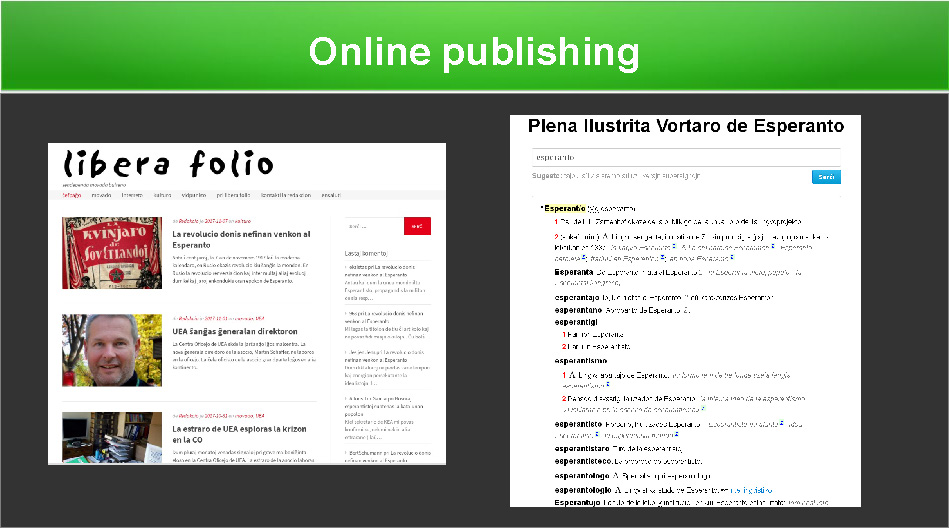

- the web magazine Libera Folio (Free Folio or Sheet or Page), established in 2003 by a Finnish Journalist (Kalle Kniivilä) and a Hungarian translator (István Ertl); it focuses on news from within the international Esperanto movement;

- the gigantic monolingual dictionary “Vortaro.net”, an electronic version of the aforementioned largest, printed monolingual dictionary (Nova Plena Ilustrita Vortaro de Esperanto / New complete illustrated dictionary of Esperanto) published by SAT; and

- the Esperanto version of Wikipedia with currently (2019) more than 271,000 articles

Publishing Statistics

Let me give you finally a bit of statistics, at least with regards to printed books, so that you can get a better idea of the WHAT and the WHERE.

The largest reseller of Esperanto books is Universal Esperanto Associaiton, UEA. It’s book store (locally in Rotterdam, The Netherlands, but also online), listed in 2018:

- 7689 different items, i.a. 6882 different book titles

- written by 3335 authors and co-authors

- sold to UEA by 1901 publishers

- 2160 second-hand books and 6007 second-hand magazines from older periods of the Esperanto movement.

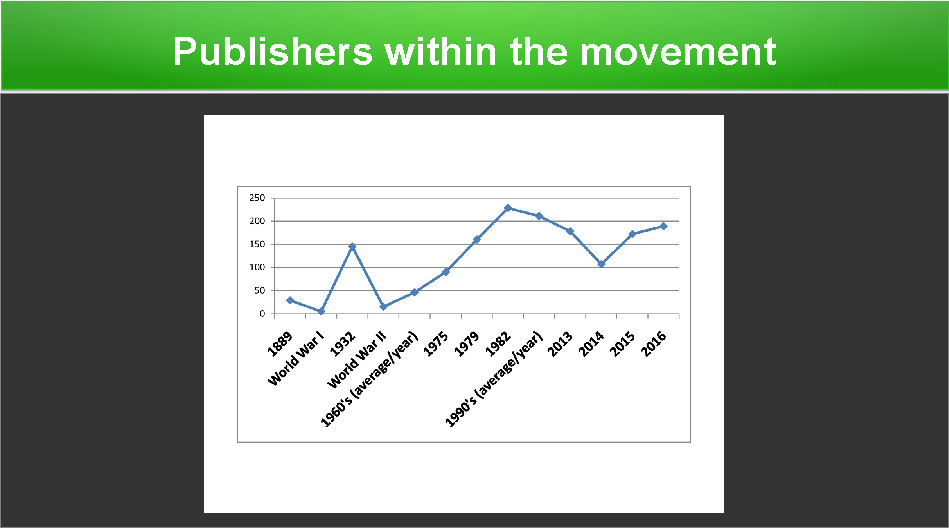

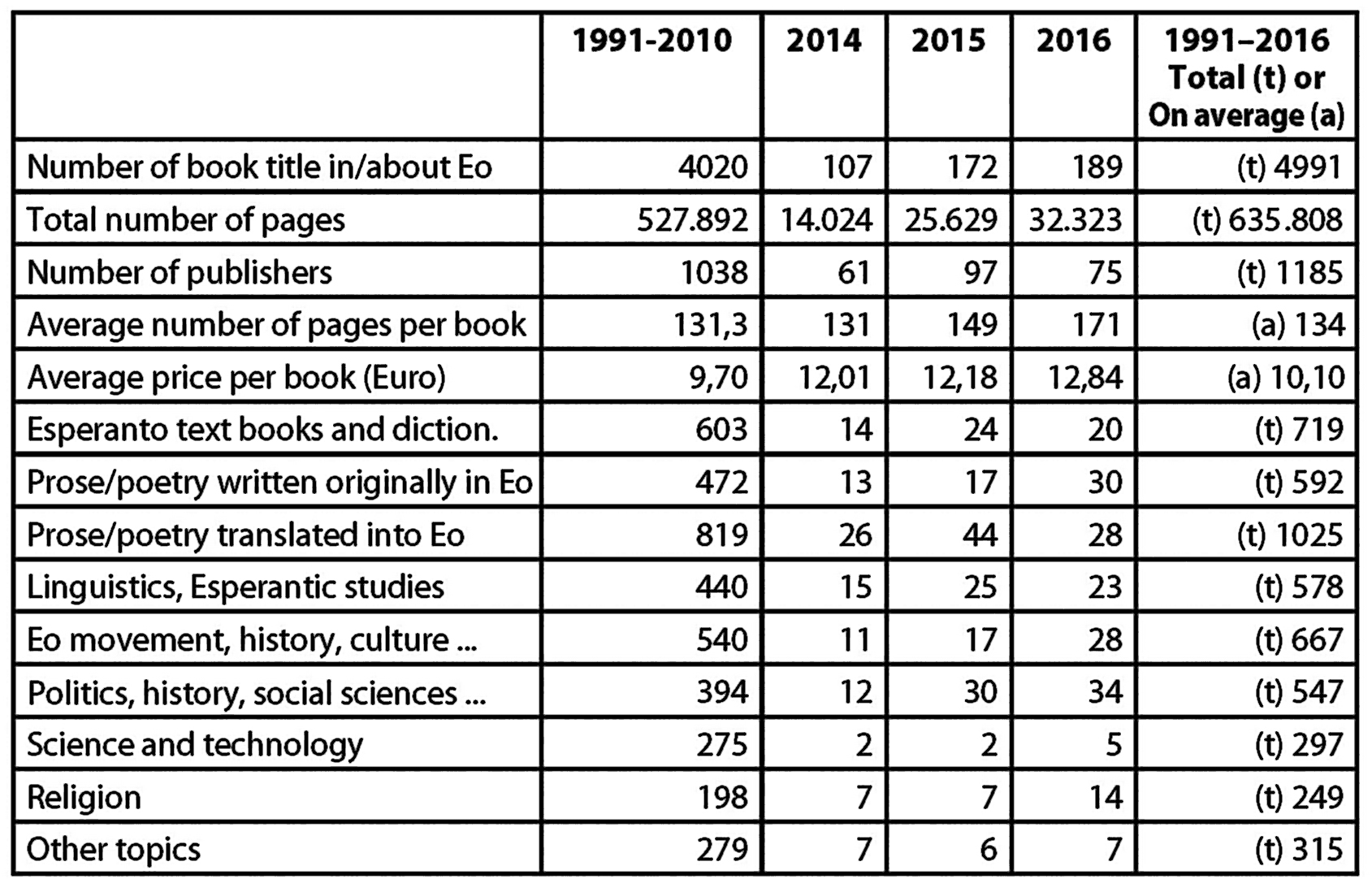

This graph shows the ups and downs of book publishing in the past 130 years. (Source for this and all following statistics: La Ondo de Esperanto, Kaliningrad, Russia)

The numbers at the left indicate how many different book titles were published that year. You can see a first culmination point between the two world wars. After Zamenhof’s death in 1917 and the end of World War 1 in 1918, Esperanto became so popular that in 1920/21, the League of Nations considered for a while to officially adopt it as an official international language. After World War 2, the movement and it’s literary production grew again, slowly but constantly, and interestingly, during this time of the cold war, most esperantists lived in Eastern Europe, and most of the big international Esperanto events, cultural and others, happened there behind the Iron curtain, with, at the same time, Esperanto spreading also, again, in Asia, Latin America, Australia and, to a lesser extent, in Africa. With the big political changes in Europe in 1990 and the growing economic problems of the peoples in Eastern Europe at that time, Esperanto took a big hit, and the number of organized speakers as well as the number of books published, declined. This process was reversed again when the Esperanto community fully discovered that they could take advantage of all the possibilities that the Internet has to offer, like distribution of Esperanto books through non-Esperanto online distribution channels like Amazon.com, or the distribution of eBooks. This came late, in comparison to the outside world, because (a) Esperantists are kind of conservative whith regards to changing habits, changing cultural traditions, changing distribution channels for books, changing reading habits (from print book to tablet) etc. But also (b), because a large number of Esperantists live in countries or societies of the world, where it is still today somewhat hard to gain regular access to the Internet – there are, for example, large groups of Esperanto speakers in, say, Nepal, in Vietnam, in remote areas of Brazil and other Latin American countries, in Africa, in Cuba, in China, etc. Many of them still need to receive printed materials, in order to be able to read Esperanto.

Now, let’s take a closer look at the print books statistics of the past 25 years:

This first table above tells you WHAT has been published.

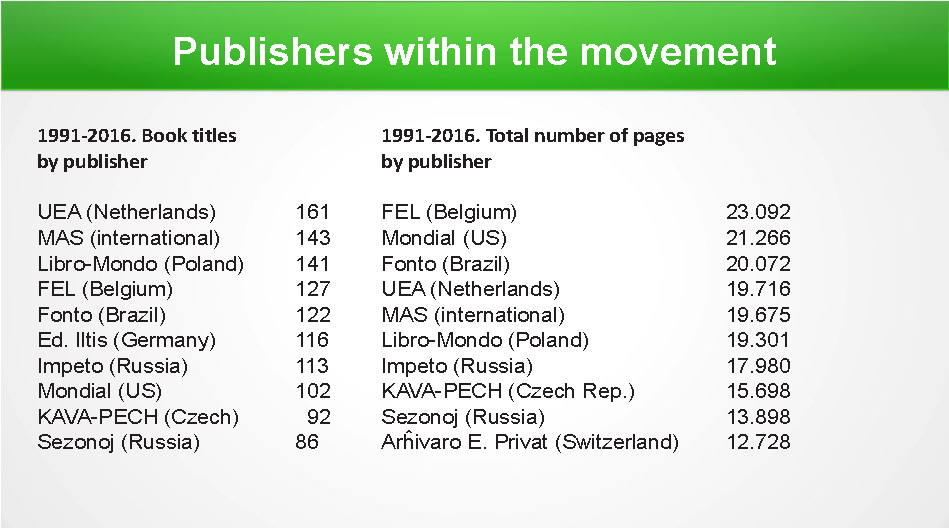

You can see here that the 10 most active current publishers come from Europe, Brazil, and the US. On the left, you have the number of book titles published by each publisher over 25 years. On the right, the publishers are sorted the by page numbers, which can give you an impression which publisher produces mostly brochures, novellas, small poetry books etc., and which publishers produces quantitatively more impressive titles, like novels, larger dictionaries and encyclopedias, larger essay collections and so on.

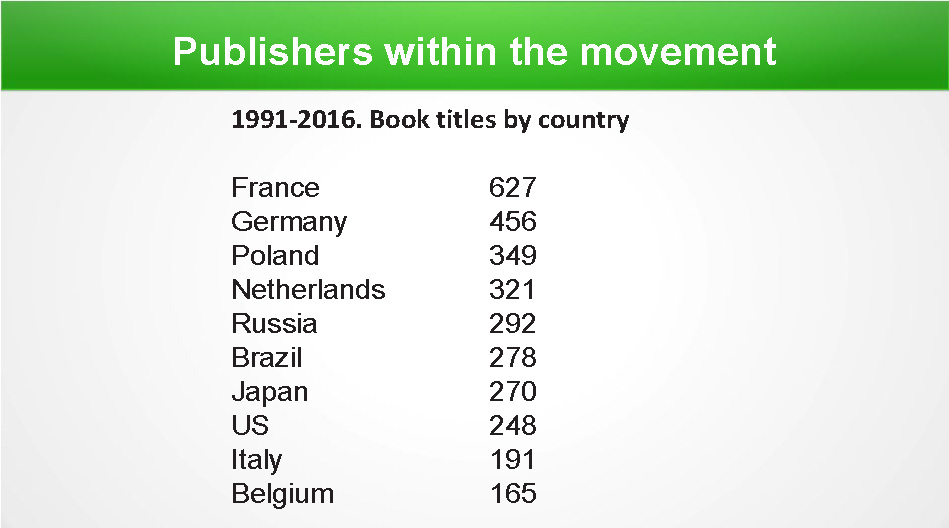

If you look at the total number of book titles per country, you get a rather similar table. The main reason for a different order of countries here is that some of them have more than one active publisher and others don’t:

In total, during these 25 years, Esperanto books were published in 75 countries of the world. But only 29 of these countries produced at least one title in each of these 25 years.

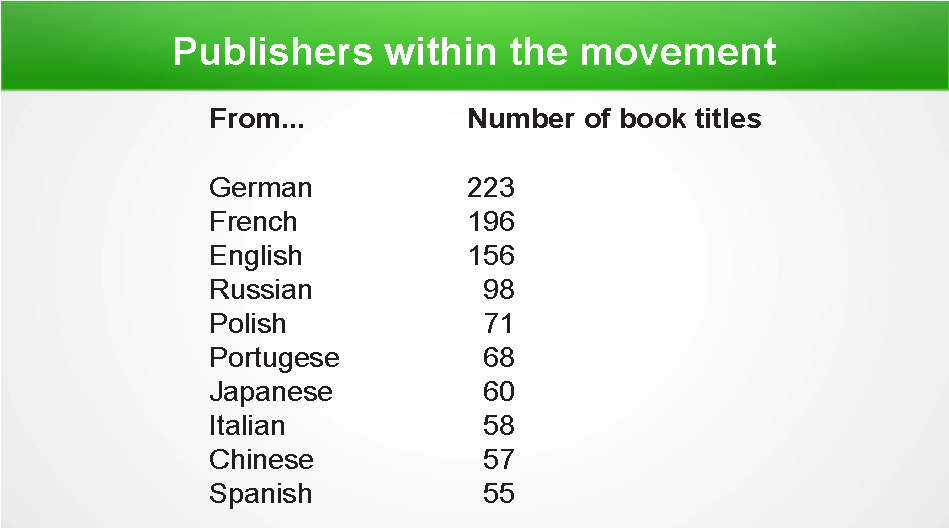

With regards to translations from national languages, here is the list of languages translated most into Esperanto during these past 25 years:

In addition, it is worth mentioning that during the same time period of 25 years, 153 books were translated FROM Esperanto into national languages.

Thank you!

After all these numbers, let me finish with a quote.

I mentioned at the beginning that often outsiders, once they get to know Esperanto better, become enthusiastic about it. Here is one of them, Esther Schor, an American poet, author, and Professor at Princeton University, who, a while ago published her book “Bridge of Words”. She said in an interview with Jamie Saxon, published on the website of Princeton University:

Zamenhof knew that language could be both a precious, shared treasury of culture, and a barrier between cultures. He envisioned Esperanto as an auxiliary language, that is, a second, helping language for the world; it was never meant to replace national languages. Though he was an ardent idealist, for tactical reasons he initially pitched Esperanto in 1887 as a language of progress: commercial, intellectual and intercultural. He represented it as a technical innovation that would save both time and money. At the same time, he included two original poems (his own) in the initial pamphlet, asserting that Esperanto would make world literature newly and widely accessible across linguistic boundaries. He likened Esperanto to a plank that lay on a riverbank; people would find all sorts of reasons not to put it in place, but sooner or later, common sense would dictate that the plank be used to bridge the stream.

(Princeton University website; Nov. 11, 2016)

I thank you all very much for your patience and attention.